For centuries, sharecropping was not only a form of agricultural management, but an integral part of the local identity, on which the social, economic, and landscape organization of Montalcinello was based. A complex system, founded on very specific agrarian agreements, which regulated the lives of farming families until the 1960s. The dynamics and importance of this system have been reconstructed by the local historian Evaldo Serpi, through direct testimonies and archival documents collected in his book Vita contadina.

The pact of the countryside: sharecropping and the identity of Montalcinello

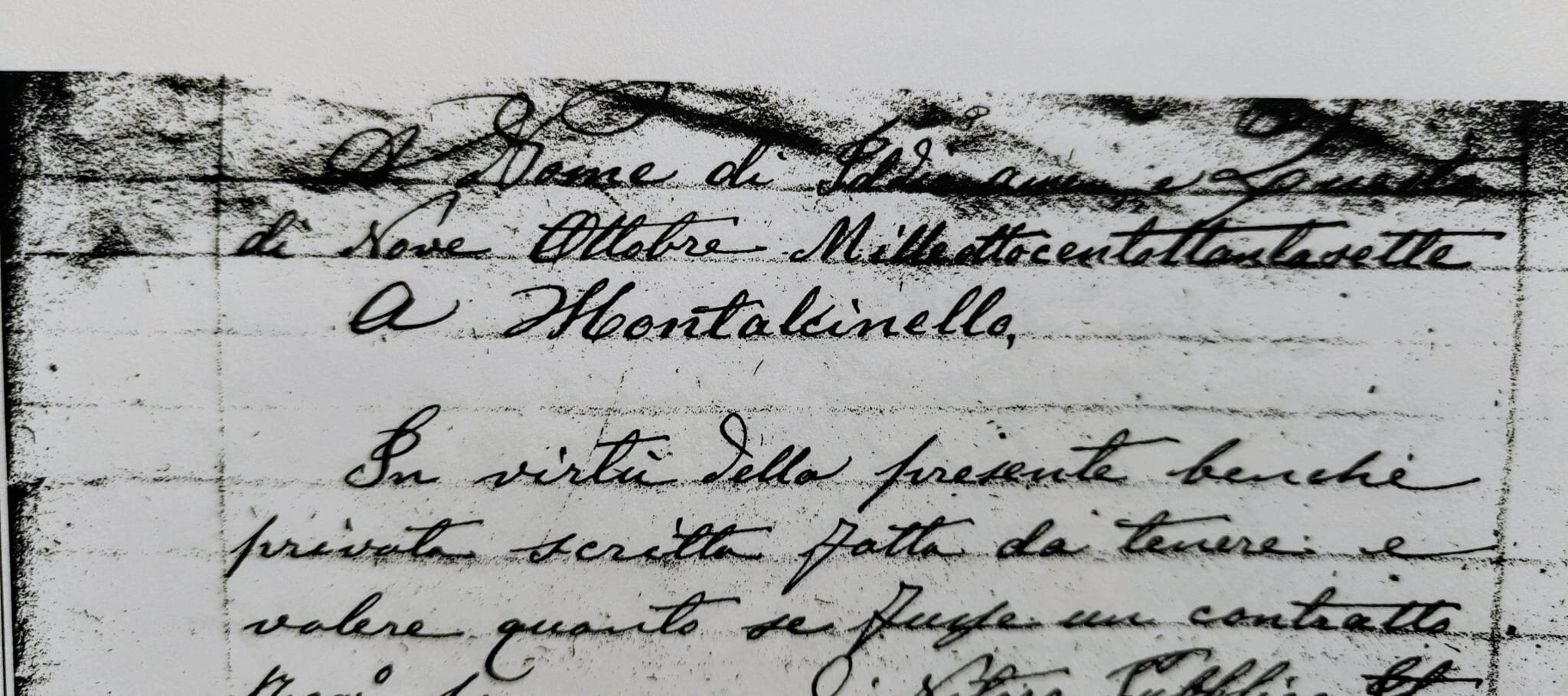

Sharecropping, present in Tuscany at least since the end of the 14th century, found one of its deepest roots in Montalcinello. Here, the relationship between landowner and sharecropper was not limited to the cultivation of the land, but translated into a precise system of rules, capable of regulating every aspect of agricultural production and the lives of the workers. The agrarian agreements were the core of this mechanism: real contracts that established rights, duties, resources, and working methods. Through these agreements, the agricultural work calendar was defined, the division of tasks, the amount of seeds to use, the management of livestock, and the distribution of products. Wheat, wine, legumes, wool, and oil were divided equally between landowner and sharecropper, according to a rule that gave the system its very name. However, the rigidity of the contracts and the accounting mechanism often kept the farmer in a condition of economic dependence, with debts accumulating year after year. This agreement, drawn up by the steward, was automatically renewed and read to the head of the family upon arrival at the farm. The signature, often a simple “X,” marked the acceptance of an agreement that regulated not only work, but the entire existence of the family. As Serpi points out, the farmer lived under a strong constraint: free time was almost nonexistent and every ounce of energy was devoted to the productivity of the farm. The agrarian agreements guaranteed the large landowners—nobles, religious institutions, and the urban bourgeoisie—stable and relatively secure incomes, based on food production. At the same time, they ensured a capillary management of the territory, maintaining a productive balance that lasted for centuries.

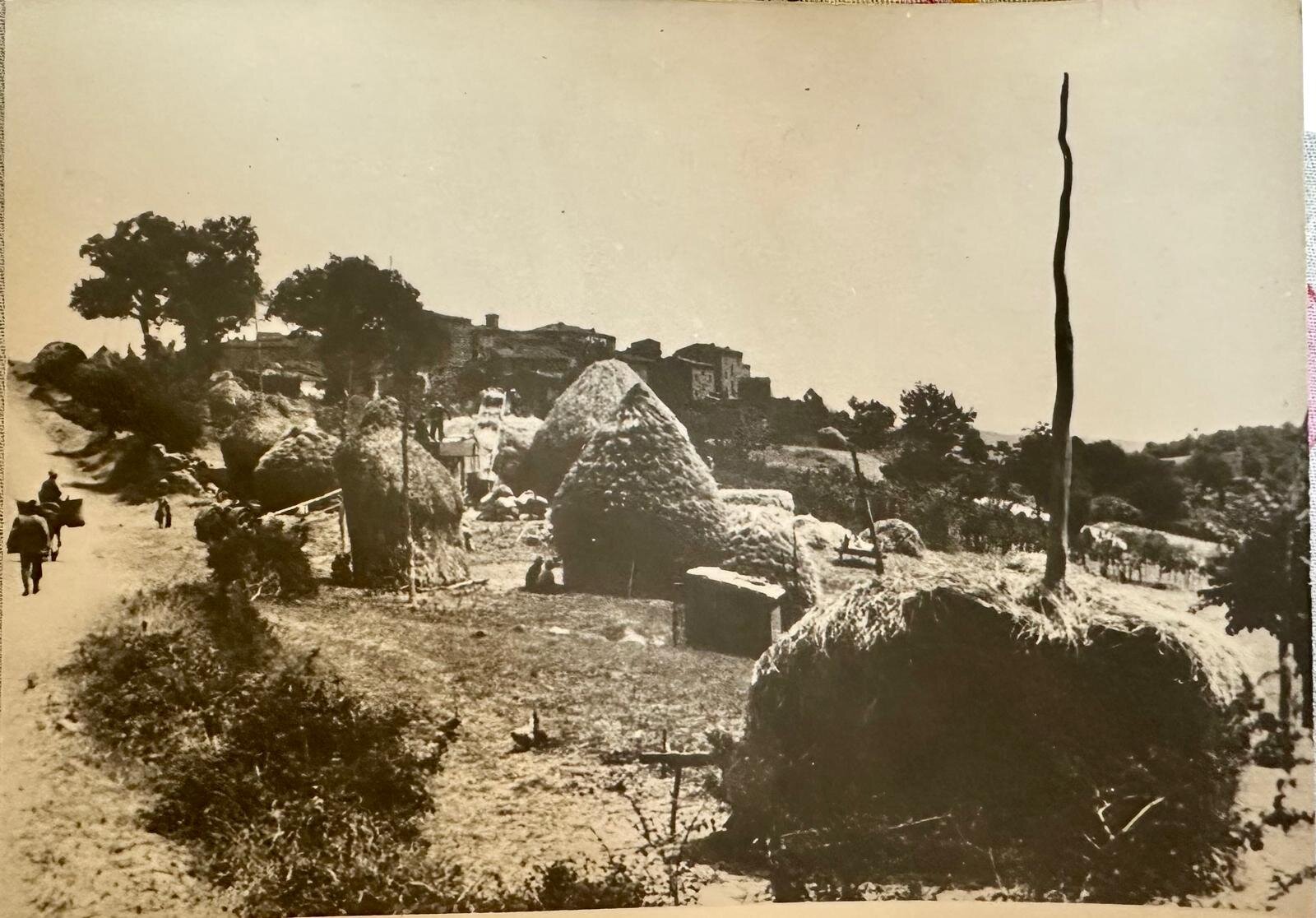

The documents collected by Evaldo (often coming from private archives or passed down from father to son) give us the image of a countryside governed by the rules of landowners (called "padroni") and by the hard work of the peasants and their lives dedicated to the farm. The "brogliacci," registers in which income and expenses were recorded, represented an essential tool for control and management. A point of reference in this context was the General Convention Project for the colonies of some provinces of Tuscany from 1869: a text of 79 articles that codified sharecropping in accordance with the Civil Code of the time. Even the mobility of sharecropping families was dictated by agricultural agreements. At the end of the contract, often in spring, the move to a new farm would begin, after an inventory of what was left behind. The centrality of sharecropping also emerges in the layout of the village: under each house were the animals, an essential element for survival and productivity. More livestock meant more cultivable land and greater possibilities to support the family. The landscape itself, made up of fields, farms, and sheds, was the direct result of this lifestyle.

Montalcinello seen from the cemetery lane (c.1940)

Today, with the end of sharecropping and the transformation of the countryside into a tourist and specialized area, this system has been surpassed. Yet, understanding the centrality of sharecropping and its agrarian agreements means reading the deep roots of the landscape and understanding the identity of Montalcinello, recognizing how the contractual history of the land has shaped the territory.

Source: Serpi E., “Peasant Life - Agrarian Agreements”.

Source: Serpi E., “Montalcinello: origin and events of a community”, 1997

“The Farmer”

by Evaldo Serpi

That old man has always been a farmer

And now, for better or worse, he is a city dweller.

He thinks that no other generation

Will ever witness this transformation again.

His experience as a farmer is now over

Because he is forced to live another life.

So many memories come to his mind

Of when the countryside was full of people.

After elementary school

He would take the animals out to graze.

He walked with iron-shod shoes

Both in winter and in summer.

On Saturdays he would give them a polish

To go to mass on Sunday morning.

When there was wheat and corn

One way or another, they made it to the new season.

All the men clinging to the little sunshade

Would carry a small sickle behind them.

To support the scythe and the billhook

When they worked during the day.

In the countryside at every moment

They were exposed to rain, cold, and wind.

In summer, with the great heat

They suffered the Lord's torments.

When the wheat in the fields was dry

Groups of people would reap it by hand.

Now many fields are abandoned

Even the farms have collapsed.

Even for the most important holidays

Everyone always worked.

Now I'll tell you quickly

They would take care of the animals and then celebrate.

What was inhuman

They always had to stay humble, hat in hand.

Without permission they couldn't even gather a bundle of sticks

Otherwise they would be called in by the next morning.

Because it was written and clearly specified

In the document they had signed with the landlord.

How you had to behave throughout the year

And even during the day.

When Christmas came

They would bring chickens and pork to the landlord.

And at Easter, always to the landlord

Baskets of eggs and a nice capon.

He and his family would eat and drink

And whatever was left over, he would sell.

While all the poor farmers

Would crane their necks, old and young alike.

They were considered a bunch of ignorants

But many sought after their tools.

They put them on display in the museum

To make a few million out of it.

They exploited them when they were farmers

And now with their tools they make money.

Source: Serpi E. “Let’s have a laugh before the day is over - Collection of rhyming stories,

nursery rhymes and various jokes” 2007, Siena.