When warmth is an achievement: the history of heating in Montalcinello

For centuries (indeed, in the case of Montalcinello, for millennia) the hearth has been the heart of homes: it was used not only for heating, but also for cooking and bringing the family together on cold winter evenings.

Wood, such as that from the holm oak (in Latin licinus, from which the name Montalcinello originates: Mons licinus, mountain of holm oaks), abundant in the surrounding woods, has always represented the main source of heat for the families of the village and the Val di Merse in general; just as the biting cold has always characterized the winter months of the village, especially on its northern side, hidden from the sun, which descends from the square down to the Scogli and the Fiumarello.

The north side of Montalcinello seen from Campaione

Heating the village: history and transformation of heating systems

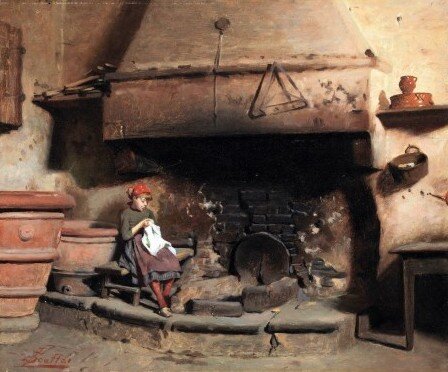

The ancient houses of Montalcinello had large fireplaces, differing according to the type of dwelling and use. Among the most famous is the fireplace with seats, typical of large farmhouses or larger village houses, so big that it was possible to sit inside it, on either side of the fire.

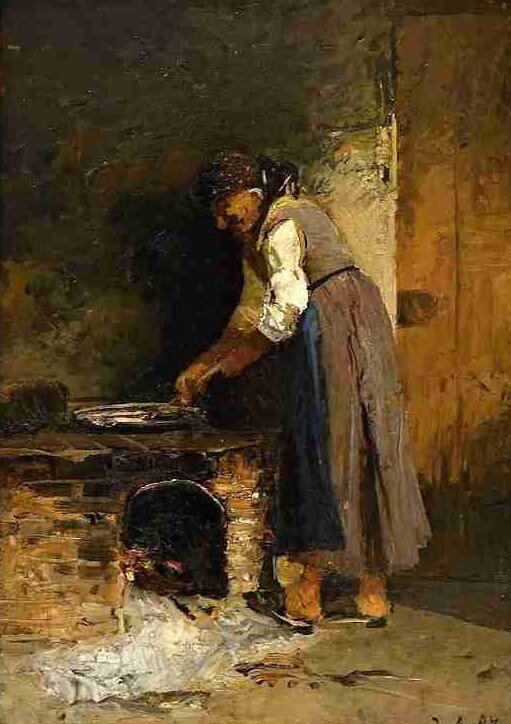

Another widespread hearth was the raised one with a triple brazier: a large one in the center with a hook for the cauldron and two smaller braziers on the sides; it is considered the most direct precursor of the cast iron kitchen stove. Kitchen stoves began to spread first in masonry (by transforming the hearth with an increasingly raised brazier up to the height of the current cooktop), then in cast iron around the nineteenth century, with many versions and evolutions, in some cases surviving as vintage objects and more rarely still in use. Other types of stoves were used to support the kitchen stoves in other rooms of the house, such as those made of terracotta, cast iron, and later those fueled by kerosene.

Cast iron stoves were produced in all possible shapes, from wide ones with multiple plates to narrow ones with a single door, from those with an oven to those in majolica (rare and expensive). Stoves were placed everywhere: in the corridors of houses, at school, in cellars, and in craft workshops, gradually becoming an omnipresent object. Many had a small sheet metal radiator along the flue, and others had iron wires for hanging damp rags. In bedrooms, the biting cold of the night hours was tempered with coal bed warmers, such as the famous “prete” shaped like a sled.

At the end of the twentieth century, especially in the eighties, it was the era of radiators: initially powered by wood-fired boilers and later by diesel first and then by LPG; they made homes more comfortable and evenly heated. Today, finally, it is time to return to the earth and sustainability, with the geothermal heating network that by 2026 will heat the village's homes.

The heat of the earth: from fire to innovation

Already in the nineteenth century, in nearby Larderello, underground steam was used to produce energy. In 2026, thanks to the constant strengthening of the geothermal heating network, Montalcinello will also have the opportunity to heat itself with this ultra-sustainable source. A return to the earth after centuries of fire and fuels. District heating is in fact an important turning point for the village in several respects.

From an environmental point of view, district heating eliminates the emissions produced by the fuels used so far, improving air quality as it is a renewable source produced locally, without transport or combustion.

From an economic point of view, the savings will be significant both for homes and businesses, no longer bound by fluctuating bills, tractors loaded with wood dumped in front of cellars, or 15kg bags of pellets carried on shoulders through the village alleys. In this way, the value of the fireplace fire will no longer be relegated mainly to a source of heating but will gain even more value as a slow and important moment to be enjoyed with loved ones.

Not only sustainability and savings, Montalcinello is preparing to warm itself with a new but its own energy, primordial yet innovative, ultra-local and clean, produced directly from its own subsoil.